Offshore Processing of Refugees

What is “Offshore Processing”?

For two decades, Australia has subjected asylum seekers who arrive by boat without a valid visa to “third country processing” or “offshore processing”. When people seek asylum by boat in Australia they are transferred to processing centres (also referred to as “detention centres”) in other countries. Those processing centres are paid for and staffed by the Australian government. Beginning in 2001, Australia sent maritime arrivals to the Republic of Nauru (Nauru) and Manus Island, Papua New Guinea (PNG). An additional processing centre was established on Christmas Island, an Australian external territory. The government paused the process in 2008 but began sending asylum seekers to Manus and Nauru again in 2012. Despite the fact that offshore processing arrangements still remain in place, no asylum seekers have been transferred to Manus or Nauru since 2014. Instead, asylum seekers are intercepted and turned back at sea or they are returned to their country of origin.

The “Pacific Solution”

Offshore processing was first introduced in 2001 by the Australian Government under Prime Minister John Howard. Australia sent maritime arrivals to the Republic of Nauru (Nauru) and Manus Island, Papua New Guinea (PNG). The policy was implemented in tandem with a practice of intercepting and turning back asylum seeker boats that entered Australian waters. Together, these practices and policies were referred to as “The Pacific Solution”. In a defining moment, Prime Minister Howard said during an election speech: “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come“.

In the early years of the Pacific Solution, those found to be refugees could be resettled in Australia. Between 2001 and 2008, a total of 1637 people were detained on Nauru and Manus Island, including 786 Afghans, 684 Iraqis and 88 Sri Lankans. Around 70% were resettled in Australia or other countries. By the end of the Howard years, the number of asylum seeker boats had declined dramatically and in 2007 the Pacific Solution was dismantled.

The Return of Offshore Processing

Growing unrest in Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran and Sri Lanka In 2009-2010 led to a significant increase in the numbers of asylum seekers trying to reach safety in Australia by boat. Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced that Australia would resume offshore processing. Transfers again began to Nauru and PNG in 2012. In 2013, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd announced shortly before an election that all asylum seekers (not just some) who arrived by boat would never be resettled in Australia.

“Operation Sovereign Borders”

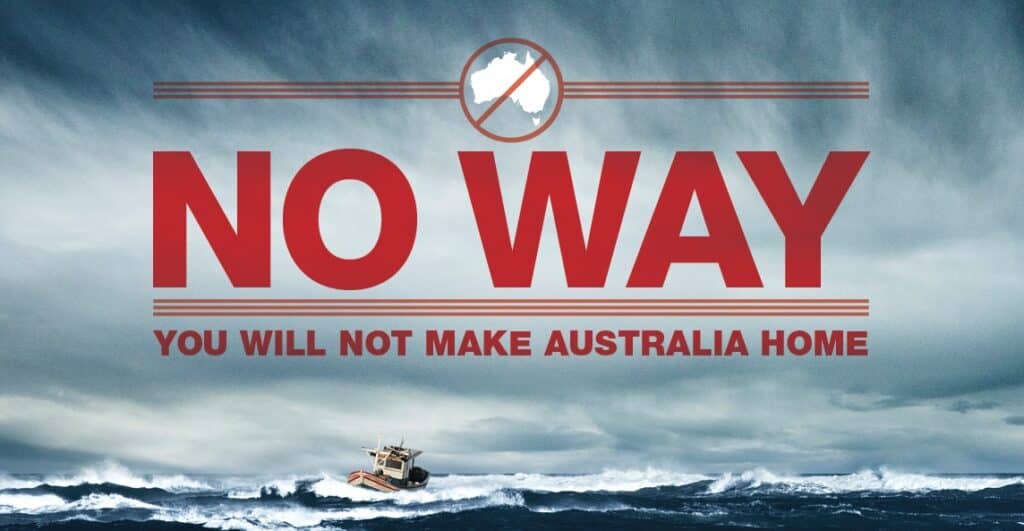

During the 2013 election campaign, the Coalition ran on a campaign of “stopping the boats”. Following their win, the Coalition and Prime Minister Tony Abbott ushered in an even harder-line border policy, “Operation Sovereign Borders”. It was implemented by then-Immigration Minister Scott Morrison, who is now the current Australian PM. The operation, under the command of a three-star general, was a “zero-tolerance” policy to what the government labelled “illegal maritime arrivals“. This included boat turn-backs, detention of maritime asylum seekers on PNG and Nauru, policies to deter people-smugglers and a significant advertising campaign in refugee source countries that urged there was “No Way” asylum seekers would ever be resettled in Australia. At its peak in February 2014, there were 1325 people held in the Manus Island centre and 1107 in the Nauru centre (including 222 children), a total of 2,432 people detained. Despite the fact that offshore processing arrangements still remain in place, no asylum seekers have been transferred to Manus or Nauru since 2014. Instead, asylum seekers are intercepted and turned back at sea or they are returned to their country of origin.

Options for Resettlement

At the time offshore processing was introduced, asylum seekers were told that they would be resettled elsewhere. However, over 8 years later, billions of dollars have been spent and hundreds are still in limbo. In 2014 Australia entered a short-lived deal with Cambodia to resettle refugees. Refugees had to choose to be resettled in Cambodia and only seven accepted this offer. The USA resettlement deal is the only current bilateral durable solution available, but this is restricted and is coming to an end. New Zealand has had a longstanding offer to resettle 150 refugees per year from offshore detention, however, the Australian government has been reluctant to take this up because after five years refugees would be able to take up NZ citizenship and travel to Australia without restrictions.

The USA Resettlement Deal

In 2016, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced a resettlement agreement with American President Barack Obama in which the USA agreed to take 1,250 refugees held on Manus Island and Nauru. Although there was speculation that the deal was done in exchange for Central American refugees coming to Australia, the Australian government has denied this. President Donald Trump initially criticized the deal, however he agreed to leave it in place while subjecting the refugees to “extreme vetting”.

The first refugees were resettled in the USA in September, 2017. In October 2020 the Home Affairs Department estimated that the resettlement deal would be concluded in March or April 2020-2021, however as of June 2021 it is ongoing. Close to 1000 persons have been resettled in the USA as part of the agreement.

The Medevac Bill and Transfers to Australia

In early 2019 the Australian government passed the Medevac Bill, allowing critically-ill refugees and asylum seekers in offshore detention to be “medically evacuated” to mainland Australia for treatment. In order to be transferred, two independent Australian doctors had to recommend the transfer and verify that appropriate treatment could not be provided offshore. The Immigration Minister had additional power to refuse any requests for transfer based on security or medical grounds. Prior to the passage of this legislation, sick refugees had to wait an average of 2 (and often up to 5) years for transfer to Australia for medical treatment.

The Australian government repealed the Medevac Bill less than a year after it was introduced; 192 persons were brought to Australia for treatment while it was operative. The government had repeatedly argued against Medevac on security grounds, with Prime Minister Morrison stating, “Someone who’s a paedophile, who’s a rapist, who has committed murder – any of these other crimes – can just be moved on the say-so of a couple of doctors on Skype.”

Refugees who were brought to Australia under the Medevac legislation were detained in “Alternative Places of Detention (APODs“, typically hotels in cities such as Brisbane and Melbourne, which are closed places of detention with no freedom of movement. While some have now been released from detention and are on temporary bridging visas (subclass E), many are still in closed detention over a year after they were brought to Australia. These persons endure extremely restrictive conditions that were also exacerbated during COVID. There have been multiple suicide attempts amongst detainees in APODs in both Melbourne and Brisbane.

A Legacy of Trauma

Offshore detention is designed to be so brutal that asylum seekers are forced into despair and agree to go back home to whatever they have fled.

There is significant documented evidence of the abuse and harm caused to those in Australia’s detention facilities. The UNHCR has repeatedly called for an end to Australian detention and the safe resettlement of those offshore. Primary concerns include:

- Ongoing and significant effects on mental health caused by prolonged and indefinite detention, including the mental wellbeing of children;

- Violence and harm from both the local community and authorities;

- Physical abuse, including that of children and LGBTQ+ persons;

- Overcrowding and inadequate shelter; and

- Grossly inadequate healthcare, including a lack of mental health supports.

The evidence of poor conditions, abuse, harm and inadequate treatment is clear; 13 persons have died including through neglect and suicide. One psychologist and traumatologist said that treatment of asylum seekers on Manus and Nauru was the worst thing he had ever seen. In 2020 the international community, including 47 UN member states, raised concerns about the Australian Government’s refugee, asylum and immigration detention policies and its human rights record. Australian offshore detention, however, continues.

Trailer for “Chasing Asylum”, Directed by Eva Orner (Source: Refugee Council of Australia)

Please note this video contains content that may be distressing to some viewers. Topics include suicide and psychological distress.